Happy violence

A form of violence that stems from self-exploitation in which the human being exercises their freedom to imprison themselves in an individualism that satisfies the demands of capital and globalisation.

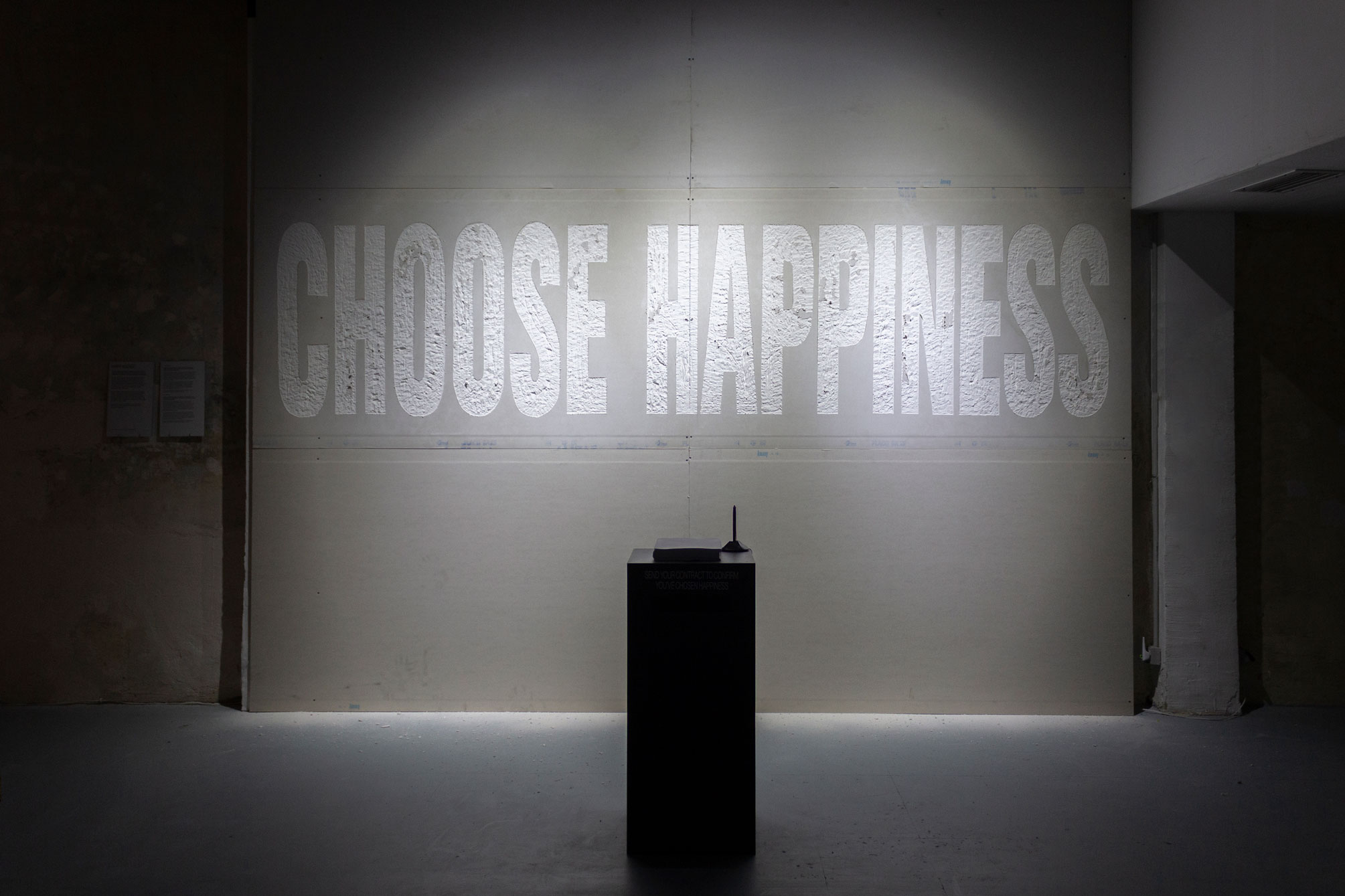

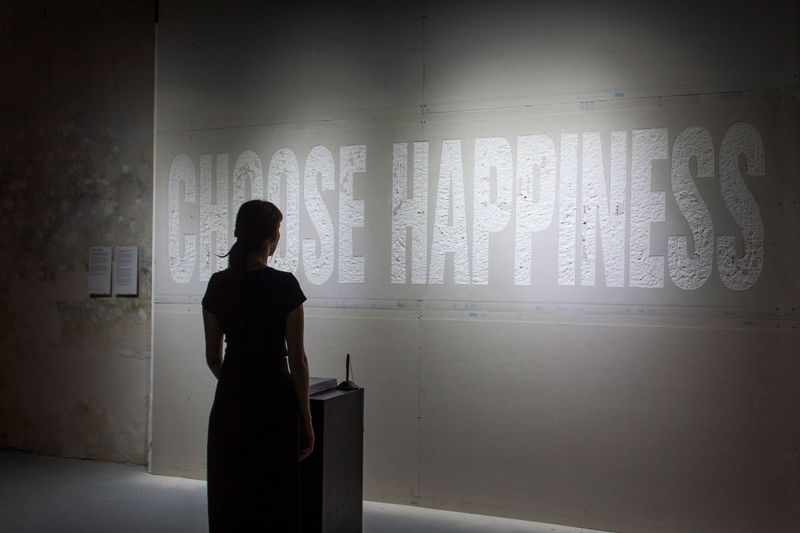

The piece

Our lives are driven by a constant promise of happiness. Of big events in life that fulfill us (momentarily?), just enough to make us strive for the next “happy moment” in our checklist: finishing our studies, getting married, buying a car, having kids, retiring… We locate happiness in certain places and construct exciting social narratives around them. But according to expert Sarah Ahmed “if we have a duty to promote what causes happiness, then happiness itself becomes a duty”.

Of course, reality is complex and our duty to find happiness can’t always be completed. Ahmed points out that happiness is looked for where it is expected to be found, even when happiness is reported as missing. In her words: “The demand for happiness is increasingly articulated as a demand to return to social ideals, as if what explains the crisis of happiness is not the failure of these ideals but our failure to follow them.”

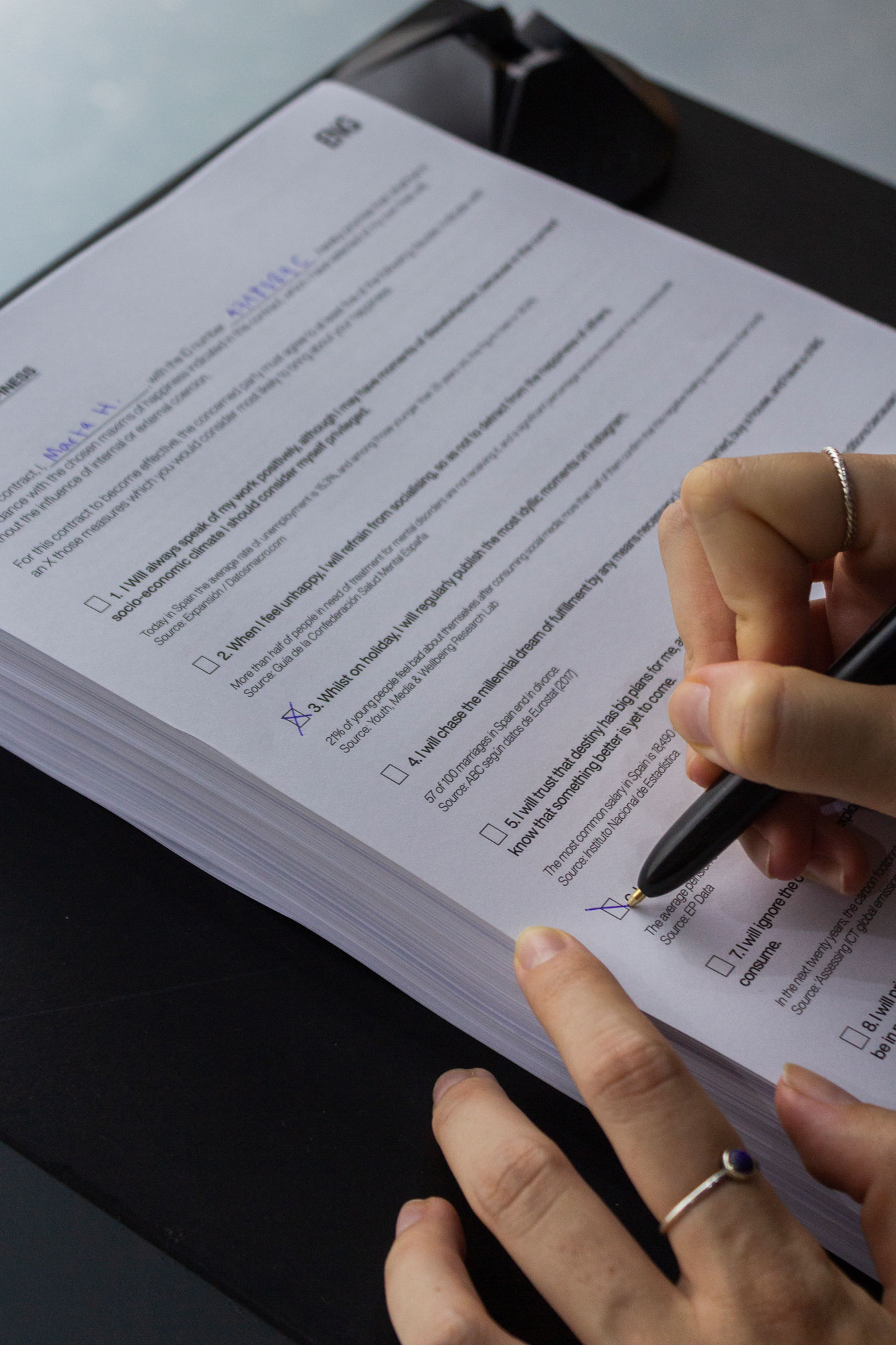

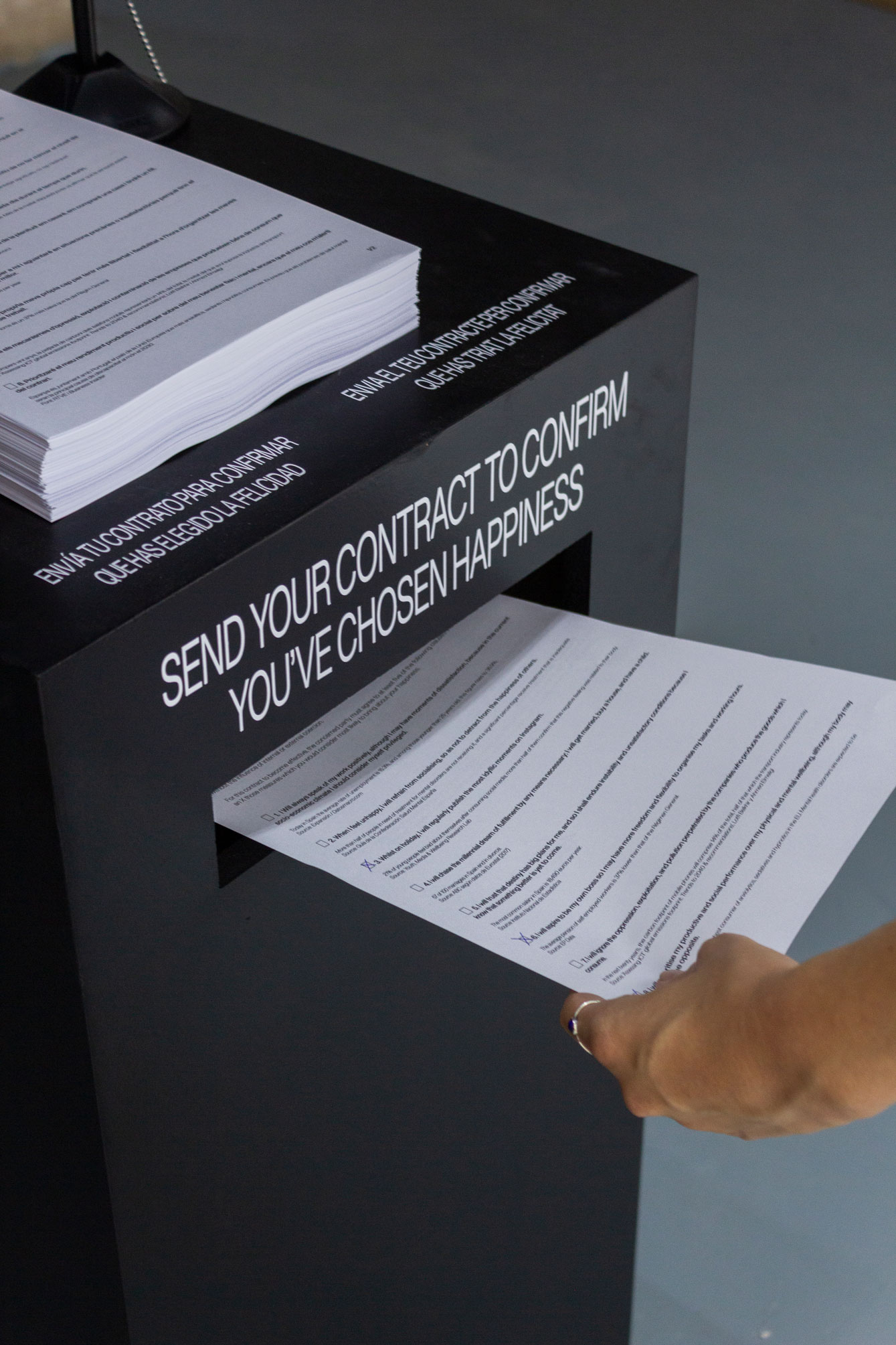

The contract of happiness contrasts two conflicting realities: the promise and the fact. What are we consenting to when we consent to happiness?

Ahmed, Sarah. (2010) “The promise of happiness”. Duke University Press.

Context

In his book “Topology of Violence” philosopher Byung-Chul Han studies the drivers that affect the use of violence both in the old and the contemporary world. According to him, in the societies that precede us, violence operated out of negativity, that is, inciting an immune reaction: defense. Today the problem would be an excess of positivity, which obfuscates all negativity and displaces violence within oneself, despite the prevailing appearances of prosperity and freedom.

While happiness shapes what coheres as a world, the work of feminist, black, and queer scholars have shown in different ways how happiness is used to justify oppression. Feminist critiques on the topic of “the happy housewife,” black critiques of the myth of “the happy slave,” and queer critiques of the sentimentalization of heterosexuality as “domestic bliss” are clear examples of that.

Still, we collectively wish for happiness. The media is saturated with images of it. Happiness is both produced and consumed through books, stories and experiences, accumulating value as a form of capital. Barbara Gunnell describes how “the search for happiness is certainly enriching a lot of people. The feel-good industry is flourishing. Sales of self-help books and Cds that promise a more fulfilling life have never been higher.”

We live to be happy (whatever that means).

Related concepts

The Science of Happiness: (Whose key figure is Richard Layard, often referred to as “the happiness tsar” by the British media). Layard argues that happiness is the only way of measuring growth and advancement: “the best society is the happiest society.” One of the fundamental presumptions of this science is that happiness is good, and thus that nothing can be better than to maximize happiness.

Hedonimeters: The presumably objective measurements of happiness used by the Science of Happiness. The existence of hedonimeters implies that happiness exists and that there is a way to quantify it.

Han, Byung-Chul (2016) “Topography of violence” Mit Press. Ahmed, Sarah. (2010) “The promise of happiness”. Duke University Press.